I woke up late on Friday morning, so I had to race out the door without turning on the radio, which is why I didn’t hear about George Harrison’s passing until I was halfway to class. It was hard to pay attention to the road after that. Maybe it was late-semester stress or sleep deprivation, but the news hit me hard. It helped that almost every station on my car radio, including NPR, played his music in tribute. It was both painful and comforting to be reminded in such a direct way of whom we’d lost.

I woke up late on Friday morning, so I had to race out the door without turning on the radio, which is why I didn’t hear about George Harrison’s passing until I was halfway to class. It was hard to pay attention to the road after that. Maybe it was late-semester stress or sleep deprivation, but the news hit me hard. It helped that almost every station on my car radio, including NPR, played his music in tribute. It was both painful and comforting to be reminded in such a direct way of whom we’d lost.

I remember the night when the Beatles made their network TV debut. I came to school that morning to find everyone in the playground buzzing about that new singing group from England. Only I didn’t know that it was a singing group – no one bothered to mention that part to me, so for most of that morning I wondered why Ed Sullivan would want to show a bunch of insects on his show.

By the time recess rolled around I had been told what all the fuss was about, and I returned home after school primed for an EVENT. I wasn’t disappointed. It’s hard to imagine in this YouTube world what kind of impact the Beatles made on an unsuspecting generation back then. Pop music up until that point was very, very tame, unless you were an Elvis fan; and of course black musicians were off of the AM radar for most of us lily-white kids. For the most part it was all Sandra Dee, Annette Funicello and Bobby Darin, all the time. (My best friend in grammar school was a Connie Francis fan, for God’s sake. Boy, the thought of that really makes me feel old…)

But John, Paul, George and Ringo changed all that, literally overnight. The next morning every fifth-grader in the schoolyard was singing “Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!“ at the top of their lungs, sporting guitar-shaped plastic pins with a tiny photo of our Beatle-of-choice in place of the sound hole. “I can’t tell them apart“ was the refrain from my Dad. “How do you know which is which under all that hair?“

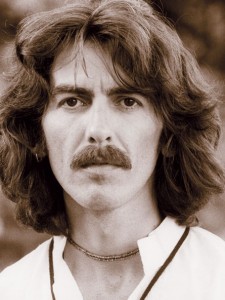

But boy, could we ever tell them apart. Most of my friends had their favorite, and George was the one that I loved. I found John’s aquiline nose and narrow eyes just a bit sinister, and Paul was too pretty to be real. Ringo had a goofy, puppy-dog cuteness about him that was appealing, but he still couldn’t hold a candle to George’s killer cheekbones. His intense brown eyes and infrequent, toothy, thousand-watt smile were a lit match to the dry tinder of my prepubescent lust, and I swore that someday if I couldn’t marry him (he was only ten years older than me – I could dream, couldn’t I?), then I would marry someone just like him, someone as talented, who radiated the same quiet intensity and intelligence.

I could relate to George. He did all the heavy lifting, guitar-wise, content to stand back in the group and let John and Paul shake their heads and make goo-goo eyes at their screaming fans. He would just play, occasionally lifting his head from the fingerboard to gaze off into space as if to remind himself where he was, reacting rather than acting, a spectator to his own fame. When it was time to sing harmony he would wait until the last possible second, and then suddenly step forward to the mike and match John or Paul note for note, only to step back again as if embarrassed at his own boldness.

It was in character. George didn’t call attention to himself. While he was the first of the Fab Four to discover Indian music and Eastern mysticism, it was the other Beatles and their musical contemporaries whose names made the headlines during their pilgrimages to the Maharishi. George learned sitar, and introduced it to the Beatles instrumental mix and to popular music in general, but otherwise refrained from going public with his politics beyond his organization of events like the “Concert for Bangladesh,” the granddaddy of every Live Aid concert since.

I can only guess what it must have been like to be seventeen years old and riding the tiger that was the Beatles. But he did it with class and poise, and when the group broke up in 1970, he made his only real public statement about the acrimony several years later with “Sue Me, Sue You Blues,“ a song in the same wry vein as “Taxman,“ his breakout hit on Revolver, a song which refrained from pointing fingers and which had none of the bitterness of the John/Paul exchanges.

I admired the way he kept finding new avenues for self-expression, from film production (The Life of Brian) to collaboration with other musicians (like his participation in the song “Badge“ on Cream’s Goodbye album, where he was credited as ‘L’angelo Mysterioso.’). He liked the dynamics of group effort, and his later work reflected this, from his participation in the Pythonesque The Rutles, in which he lampooned his own fame better than anyone else had done, and in the utter joyousness and whimsy of the Traveling Wilburys. Harrison never let himself get stale.

One of the difficult things about hitting middle age is that you begin to witness, one after another, the passing of the icons of your youth, the ones who in some way with their work flavored your world and formed the common reference points for you and your generation. George himself was sanguine about such things; you could see and hear it in his lyrics, most obviously the title song of his first solo effort, All Things Must Pass, an album that I took with me to UMass during my first sojourn there in 1972. I like to think that as he left the pain of his final illness behind to finally meet his “sweet Lord,“ he slipped away with that same wry but gentle smile on his face.

Goodbye, George. You helped write the soundtrack of my life. Thank you for all the music, and give our best to John.

(Originally published in slightly different form in The Massachusetts Daily Collegian.)

No comments yet